|

Last Update:

Thursday November 22, 2018

|

| [Home] |

|

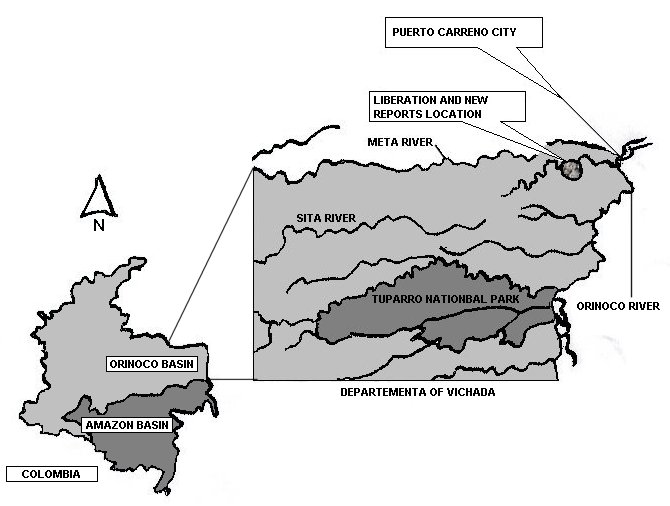

Volume 20 Issue 1 Pages 1 - 56 (April 2003) Citation: Gómez Serrano, J.R. (2003) Follow Up to a Rehabilitation of Giant Otter Cubs in Colombia. IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull. 20(1): 42 - 44 Follow Up to a Rehabilitation of Giant Otter Cubs in Colombia Juan Ricardo Gómez Serrano Director of the Ecology Program at the Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Bogota, Colombia, e-mail: jrgomez@javeriana.edu.co Giant river otters (Pteronura brasiliensis) face numerous biotic and abiotic threats throughout their geographical distribution. In Colombia, otters are also captured to satisfy the local demand for pets. Many of these pets, upon reaching maturity, become an enormous expense for the family that possess it due to the large quantity of food that the otter requires. Likewise, many otters are killed by humans due to a fear of their considerable size and strength. During the field phase of the Bojonawi Project (Ecology of the Giant Otter (Pteronura brasiliensis), in the Bita River, Vichada Colombia [Orinoco basin] (1997-1998)), rehabilitation and release of two Giant River Otter cubs was undertaken. Two investigators associated with the OMACHA Foundation carried out this activity over a period of 7 continuous months. Since this activity was not formally developed beforehand, it was mainly a case of trial and error. Due to a lack of information and financial resources, our actions depended on situations at the moment, but we always tried to make decisions that were for the benefit of the otter cubs. One of the pups (Ñamñam), a female, was received at approximately 2 months of age and she participated in the program for a period of 6 months until her liberation. We know for sure that this cub was adopted by a wild otter family that resided within the study area, adjacent to the NIMAJAY Ecoturism Campsite that also served as the base camp for the larger study on giant river otter ecology (Fig. 1). The second cub came from a small village (Cumaribo, Vichada) and was offered to us as a pet. However, after a long talk with the owners, she was donated to us, at no cost, for rehabilitation. After five years, in May 2003, I had the opportunity to visit the Bita River again and, of course, I looked forward to reports and clues about this giant otter in particular. Happily, I received three reliable reports that indicate that this not so young otter (6 years old), is now the head (alpha female) of one small group comprising four otters, two adults and two juveniles (probably her cubs). These reports come from two local fishermen that were involved in the former activities of the OMACHA foundation, and constantly visit the zone as part of their fishing activities. The other report came from a young ecology student from Bogota, Colombia, who is carrying out a study on pink dolphins and manatees in the area. All three describe the neck mark, it's unique behaviour (not afraid of people, and on some occasions gets very close to the boats), and all three locate the animal in a small lagoon and in a defined part of the river, very near to the place where the liberation was made (none of the three persons knew the exact location of its liberation).

As a preliminary conclusion, the rehabilitation process appears to have been successfully achieved, i.e. that the individuals were capable of surviving and behaved as normal wild giant otters, completely independent and able to breed. I can also confirm, therefore, that the physical and biological rehabilitation of Giant Otters is a hard and difficult process, but possible. I suggest that the success was due to five major factors:

Further to this, I would make one recommendation; that an effort is made to gather together all experience and knowledge related to captive breeding, physical requirements, behavior, rehabilitation, and threats for otter species, and for the giant otter in particular, in order to provide protocols to help or guide new efforts in giant otter conservation. Acknowledgements - Special thanks go to Clímaco Unda and Roamir, the two local fishermen who have kept an interest in the project since 1997. |

| [Copyright © 2006 - 2050 IUCN/SSC OSG] | [Home] | [Contact Us] |