IUCN/SSC Otter Specialist Group Bulletin

©IUCN/SCC Otter Specialist Group

Volume 37 Issue 1 (January 2020)

Citation: Allen, D., Devoile, J., Nobajas, A., Pemberton, S., Webb, D., and Wright, L.C. (2020). Fenced Fisheries, Eurasian Otters (Lutra lutra) and Licenced Trapping: an Impact Assessment IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull. 37 (1): 38 - 52

Fenced Fisheries, Eurasian Otters (Lutra lutra) and Licenced Trapping: an Impact Assessment

Daniel Allen1,2*,Jake Devoile3, Alex Nobajas1, Simon Pemberton1, Dave Webb2 and Lesley Wright2

1Geography, Geology and the Environment, Keele University, ST5 5BG. UK

2UK Wild Otter Trust, Little Slade, Umberleigh, North Devon, EX37 9RQ. UK

3Angling Trust, Ilkeston, Derbyshire, DE7 5GF. UK

*Corresponding Author: e-mail: d.allen@keele.ac.uk

Received 6th January 2019, accepted 3rd September 2019

Abstract: The endangered Eurasian Otter (Lutra lutra) became a protected species in England and Wales in 1978. The gradual recovery of the species coincides with the rise in specimen fishing on stillwater fisheries and increased concerns about predation. Although otter-proof fencing has been identified as the most effective medium-long term solution, the lack of a formalised legal mechanism to remove otters from fenced fisheries compromised livelihoods and otter welfare. Recognising this, the UK Wild Otter Trust (UKWOT) successfully lobbied for a licence to humanely trap and remove them. This paper examines the initial media and stakeholder responses to Natural England introducing the CL36 ‘Class Licence’ to live capture and transport Eurasian otters (Lutra lutra) that are trapped in fenced fisheries to prevent further damage. The paper analyses the UKWOT ‘Interventions Spreadsheet’ for the three years of the CL36 licence (November 2016 to June 2019) and the AT Fishery Management Advisors (FMA) ‘Otter Log’ (March 2017 to March 2019), to trace otter-related enquiries. Finally, the paper assesses the impact of the licence in practice, with reference to the successful live trapping and removal of otters from fenced fisheries.

Keywords: Eurasian otters, CL36 Licence, Fenced Fisheries, Predation, Trapping, England, UKWOT, Angling Trust

INTRODUCTION

Endangered in England from the 1970s (O’Connor et al, 1977; Chanin and Jefferies, 1978; Chanin, 1985; Kruuk, 2006), the Eurasian Otter (Lutra lutra) became a protected species in England and Wales under the Conservation of Wild Creatures and Wild Plants (Otters) Order 1977 in 1978. With added protection under the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981, Conservation of Habitats and Species Regulations 2010, and as a European Protected Species (EPS), otter populations gradually recovered (Lenton et al., 1980; Strachan et al., 1990; Strachan and Jefferies, 1996; Crawford, 2003; Crawford, 2010). During the First National Otter Survey of England, for example, only 170 of the 2,940 sites (5.8%) surveyed showed evidence of otters (Lenton et al., 1980); this increased to 1726 (59%) on the Fifth National Otter Survey of England (Crawford, 2010).

Recreational angling is worth an estimated £1.4 billion a year to the English economy (GOV.UK, 2018). During the relative absence of otters, specimen fishing on stillwater fisheries became the most popular and most profitable form of angling in England (Allen and Pemberton, 2018; 2019; Angling Trust and Institute of Fisheries Management, 2018; Paisley and Heylin, 2019) – there are now 9,546 registered stillwaters in England (Allen and Pemberton, 2019).

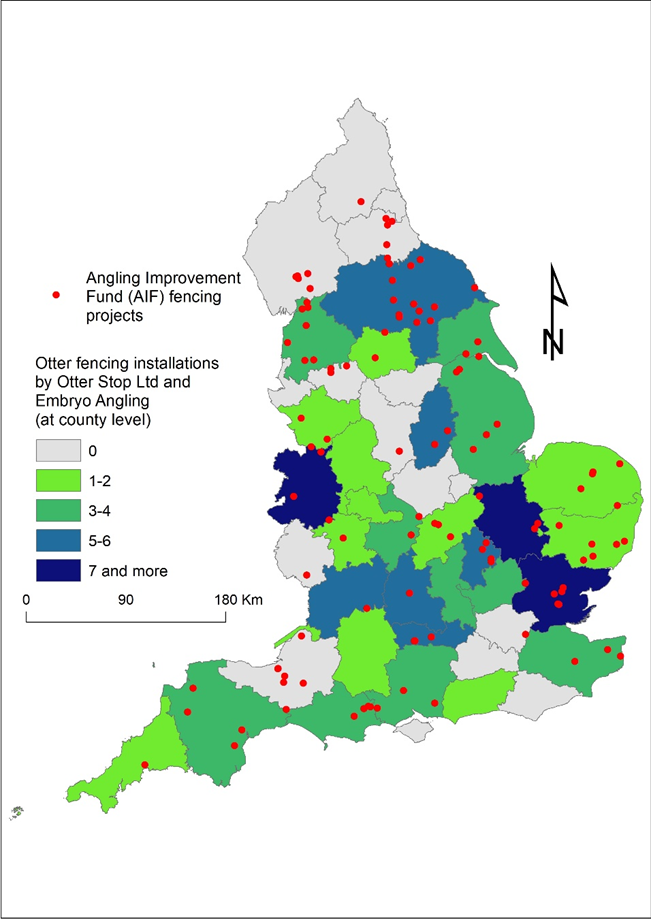

Coinciding with the recovery of an apex predator, “there has been increased concerns about predation” (Crawford, 2010 no pagination), with otter-proof fencing identified as “the only effective long term solution” (Jay et al, 2008 p. 3) to prevent otter predation on stillwaters. This has led to commercial enterprise in the form of otter-proof fencing businesses, with the largest two companies installing the equivalent of over 37 miles of fencing (Otter Stop Ltd) since 2013 and over 26 miles (Embryo Angling) since 2015. Figure 1 is a collation of the fencing projects (121 sites) publicly listed on the Otter Stop Ltd (89 sites) and Embryo Angling (32 sites) websites - this gives an indication of the geographic spread of otter fencing installations across England by these two companies alone. It is worth noting there are hundreds of other stillwater fisheries which have been fenced by alternative fencing contractors or the clubs themselves.

National strategies have also been established in response to reported economic losses from otter predation. A total of 120 stillwater fisheries received funding towards otter-proof fencing during the period of 2010-2018 – as shown in Figure 1. From 2010 to 2014 inclusive, financial support for otter-proof fencing was provided directly from the Environment Agency at an estimated total value of £125,000. Rod licence contributions to the Environment Agency have also been made available to fisheries through the Angling Improvement Fund (AIF). Since 2015 the Angling Trust has awarded £488,623 worth of small AIF grants for otter-proof fencing projects in England. During this time, two full-time Fishery Management Advisors (FMAs), funded by the Environment Agency through rod licence income, have been employed by the Angling Trust to “advise fishery managers on how to protect their fisheries from (avian and) otter predation, including advice about fencing” (Angling Trust, 2019).

Despite this, whenever an otter actually breached otter-proof fencing and went on to prey on specimen fish within stillwater fenced fisheries, there was no formalised legal mechanism available to remove them; hence, economic losses could continue and/or the welfare of otters could be compromised as some fishery managers and/or anglers may be tempted to eliminate them through illegal practices (Allen and Pemberton, 2019).

The UK Wild Otter Trust (UKWOT), which started as a Facebook group in August 2013 and became a registered charity (1167746) in June 2016, recognised this issue. During this time UKWOT changed from being a largely photography-centric group where members shared otter sightings and otter spotting advice, to an online community which encouraged ‘healthy debate’ between conservationists, otter enthusiasts and anglers. Working closely with the Angling Trust since 2014, it was agreed that a practical, legal solution was needed to humanely manage such situations; UKWOT then lobbied Natural England for a formal class licence arrangement (Allen, 2016). Otter specialists with trapping experience were consulted about traps and trapping, and the RSPCA agreed to provide ongoing welfare guidance and support. Financial backing came from Embryo Angling Habitats (2016) who offered UKWOT funding “on a case by case basis”, and to help “some clubs who can’t release money quickly” with fencing costs. After two years of planning and negotiations, UKWOT secured the first Natural England initiative ‘Class Licence’ to humanely trap and remove otters inadvertently trapped in fenced fisheries (Allen, 2016).

The CL36 licence “permits persons registered” “to capture and transport live Eurasian otters (Lutra lutra) for the purposes of preventing serious damage to fisheries”, “at fisheries that have been appropriately fenced to prevent access by otters.” The terms and conditions for acting under the licence set out the standards and procedures for trapping and releasing animals, recording and reporting requirements, and otter fencing specifications. Those applying for the licence must also: (i) identify where an otter has got into the fishery - it is the responsibility of the fishery to fix a broken fence before a trap is set; (ii) use appropriate live capture traps positioned away from areas that could flood; (iii) de-activate a trap if heavy rainfall is predicted; (iv) attend any trap set to capture live otters within 3 hours; (v) transport and release the trapped otter immediately outside the fishery fence after a visual assessment of the trapped otter’s health; and (vi) get the landowner’s permission before action is taken (GOV.UK, 2019a).[1]

This paper examines initial media and stakeholder engagement with the CL36 licence – including press releases from Natural England and UK Wild Otter Trust, and responses to the announcement from the IUCN/SSC Otter Specialist Group (OSG) and the Predation Action Group (PAG). The paper also analyses the UKWOT ‘Interventions Spreadsheet’ derived from a records database for the first three years of the CL36 licence (November 2016 to June 2019), and the Angling Trust Fishery Management Advisors (FMA) ‘Otter Log’ (April 2017 to March 2019) to trace otter-related enquiries. Finally, the paper assesses the impact of the licence in practice, with reference to the successful trapping of otters under licence.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Licenced trapping operatives:

Natural England set up an approved training course for otter trapping led by a qualified ecologist and bushcraft instructor. Three operatives from UKWOT, two from the Angling Trust, and one independent angler attended the one-day course in June 2016, qualifying as the first licenced otter trapping operatives in England. Further CL36 training courses have been held by Natural England adding another nine registered individuals, including representatives from the RSPCA, Natural England, and angling clubs.

Licence communication:

UKWOT press releases were published on Daniel Allen’s (UKWOT’s Media and Policy Advisor) LinkedIn profile, posted on the UWKOT Facebook group, shared through Twitter accounts @dr_dan_1 and @wildottertrust, and emailed directly to media contacts. This led to local and national media coverage [2]. Daniel Allen also presented details about the new licence in person during the IUCN Otter Specialist Group UK Meeting at the Chestnut Centre Otter and Owl Wildlife Park in Derbyshire on October 15 2016.

UKWOT ‘Interventions Spreadsheet’ derived from a records database:

A requirement of the CL36 licence is “record keeping and reporting for each site where the licence is used.” From November 2016 to May 2019, all CL36 enquiries to the charity were recorded in a database by UKWOT trapping coordinator Lesley Wright. The anonymised spreadsheet in this article is derived from that records database (UKWOT, 2019a). Trapping operatives employed as Fishery Management Advisors by the Angling Trust operate under UKWOT policy, and any CL36 trapping jobs are included in this spreadsheet.

Angling Trust FMA ‘Otter Log’:

All otter-related enquiries to the Angling Trust are dealt with and logged by the Fishery Management Advisors. A data share collaboration was set up between Keele University and Angling Trust to gain access and analyse this dataset.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Media engagement and impact:

On September 26 2016 Natural England made a public announcement on their website: “The licence will speed up the process for capturing and relocating otters that manage to get in to fisheries that have been fenced to exclude them. Having a group of trained people who can operate under the licence will avoid the need for individual licence applications. The process ensures the protection of otters.” James Cross, Chief Executive of Natural England, added: “The new class licence is a common-sense approach that will benefit both otters and fisheries – and embodies Natural England’s commitment to working with partners and safeguarding our wildlife for everyone” (GOV.UK, 2016).

UKWOT shared a press release about the development on September 29 2016. Founder and Chair Dave Webb explained: “I am very excited about this breakthrough for the UK Wild Otter Trust. It is an important step forward in otter conservation and it demonstrates what can be achieved by working alongside the angling fraternity. Otter predation can be an issue for fenced fisheries. This ‘Class Licence’ will give these fisheries and anglers an avenue to remove the trapped otter legally and humanely.” Media and Policy Advisor Daniel Allen added: “The UK Wild Otter Trust has taken a pragmatic approach to otter predation in fenced fisheries, and now offers a practical, non-lethal, legal solution to owners of fenced fisheries.” The position of the Angling Trust was included in the UKWOT press release. Chief Executive Mark Lloyd stated: “This is a welcome response to the representations we have been making to Natural England to deal with the potential problem of otters occasionally getting trapped inside the fences that have been installed on fisheries throughout the country, with support from the Angling Improvement Fund. Our expert Fishery Management Advisors will now be able to help fishery owners and angling clubs by legally trapping the animal and placing it outside the fence. The licences are another step forward in our wider strategy for managing the impact of predation on fish and fishing” (UKWOT, 2016).

Online media coverage ranged from local press coverage in the North Devon Gazette, ‘North Devon wildlife group granted ‘first ever’ licence to free trapped otters’ (Keeble, September 30 2016), to a national feature by BBC Countryfile magazine, ‘Otter problems and solutions’ (Parr, October 13 2016). On October 14 2016 Anglers Mail reported the ‘Breakthrough over otters’, stating the licence was “raising hopes the species might lose some of its ‘untouchable’ status” (Petch, 2016). UKWOT trapping operatives were also interviewed by CARPologyTV (November 21 2016), and appeared on a television item about otters and fisheries on BBC One’s Countryfile (January 15 2017). The item, which suggested there was growing pressure from anglers to cull otters, sparked public debate (Press Association, 2017). UKWOT’s policy and media advisor responded with a feature in the February 2017 edition of BBC Wildlife Magazine (Allen, online June 28 2017).

As Table 1 demonstrates, Natural England and UKWOT licence communication led to a readership of over 740,000 and the item on BBC’s One’s Countryfile was seen by almost 7 million viewers.

IUCN OSG UK response

Otter specialists showed “support for UKWOT driving forward work with the angling community”, and recognised “that this is vital to addressing conflict”. Individual members of OSG stated that the “project won’t solve conflict with fisheries as trapped otters are a small part of the issue”, but should be seen as “an opportunity to engage and educate more fisheries owners about the facts on predation, real threats to fish stocks and the need for good quality fencing as part of business planning for fisheries” (OSG UK, 2016). The development prompted discussion and the following points were raised:

- Communication of the project and licence arrangement gave the impression that otters being stuck inside fisheries is a common occurrence when evidence suggests it is rare.

- PR should make it clear that trapping is a last resort after other avenues have been exhausted. The first step should be to open a section of fence or install a one-way gate and encourage the otter to exit the fishery, as appears to be required by the licence. Flushing with humans should also be used.

- Concerns over welfare of trapped otters and lack of experience of operatives, made it essential to have a detailed protocol for dealing with welfare issues and injuries before proceeding, including consulting centres/organisations that might be asked to take in any otters unfit for release.

- It is not thought necessary at present to have a training programme beyond the number of operatives already trained as there might only be a few instances per year.

Predation Action Group response

Although principally regarded as a breakthrough, the Predation Action Group shared “some natural reservations” about the otter trapping licence on their website. These included:

- The narrowness of its scope, as the licence only applies to suitably fenced fisheries.

- The timescales involved in the trapping. Five days’ notice are required of any intended trapping – predation can damage fish stocks and livelihoods in that time.

- Undefined “failed trapping” period and lack of clarity regarding procedures if predation is ongoing and livelihoods affected. PAG favours local licenced lethal control in such circumstances: “If you can’t trap it you have to kill it, either under the terms of another licence issued by Natural England, or at the discretion of an ‘authorised person’ under the existing provisions of the Wildlife & Countryside Act, 1981.”

- The difficulty of trapping otters.

- Training – the cost (“of the order of £400, plus travel and an overnight stay”) and lack of clarity on future training intakes. PAG have “offered to fund the training of suitable applicants.”

- Cost of call-outs – “The fee for a call-out, if you don’t have your own trapper, may be as high as £500 per day, plus travel expenses, and possibly plus subsistence.” [3]

UKWOT ‘Interventions Spreadsheet’

During the first year of the CL36 licence, UKWOT received 45 enquiries from fisheries; 33 were given fencing advice. Of the 45 fisheries, 23 were fenced and eligible to apply for the licence. 10 had fencing up to the licence standard, 2 had electric fencing, and 3 had an overhang. 6 licence applications were made, 4 led to traps being set. 1 in 4 of the licenced traps led to otters being humanely trapped and removed from the fishery (Table 2).

Otters had entered fenced fisheries in various ways. This included the gate being “left open” (ID 1; ID 36), the fence being “breached” (ID 10; ID 24; ID 38), fence damage due to “vandalism” (ID 11) and “fallen tree” (ID 15), and unknown entrance points (ID 13; ID 44). Vulnerable points were also identified by operatives: “well-fenced but un-gridded culvert allowed entry” (ID 40); “gates, pipes, gate design” (ID 43); “probably got in via a sluice gate (1m diameter pipe) when gate removed overnight due to very heavy rain” (ID 45); and the usual advice of “close the gate behind you”.

Enquiries from unfenced fisheries, who cannot apply for licenced trapping, were also insightful. ID 14 “wanted help with cormorants; turned out to have otters too”. ID 39 had experienced, “heavy fish loss”, they “want to fence … but need planning permission for one stretch and the public are objecting.” ID 41 had not stocked fish into this site “since the 1960s”, and experienced “predation by 4 otters of fish stocks over the past 6 months”.

As Table 3 shows, CL36 enquiries dropped from 45 in the first year of the licence (October 2016 to September 2017) to 6 in the second year (October 2017 to September 2018). 4 of 6 enquires turned into CL36 applications with traps set at 1 site. One of these applications was beyond the CL36: “Otter seen with cable tie caught round its body (on River Stour). About to trap, but otter shook ties off so closed” (ID 46). Traps could have been set legally on welfare grounds but were not required. At the Norfolk fenced fishery where the traps were set, the otter escaped without the need for human intervention: “Otter vanished - probably climbed out over gate before gate modified” (ID 48).

In the third year of the licence (October 2018 to June 2019), there have been 7 enquiries so far (Table 4); 3 of the 7 became licence applications, traps were set at 2 sites and no otters were trapped. The owner of the Northamptonshire fenced fishery claimed an otter had “killed 20 carp up to 50lb weight, totalling 600lb, £70K loss. Also five dead swans found.” Traps were set, “fencing improved and pipes and culverts gridded.” There has been, “No otter incursion since then, but a dead carp put in an adjacent reserve was eaten by a large otter seen on camera.” At the Oxfordshire fishery (ID 58), the “Otter got in via weak section of fence at inlet where sluice broken” and was “Secured with heavy stone and concrete.”

Overall, of the 58 CL36 enquiries between October 2016 and June 2019, UKWOT recorded 13 CL36 applications, set humane traps at 7 locations and trapped 2 otters at one site. 45 of 58 (77.5%) enquiries led to knowledge exchange about otter-proof fencing.

Angling Trust FMA ‘Otter Log’

Between April 3 2017 and March 31 2019 the Angling Trust received 641 otter-related enquiries: 256 in 2017 (March-December), 276 in 2018 (January-December) and 109 in 2019 (January-March). Of the 641 records, 213 enquiries were connected to AIF applications with reference to otter-proof fencing (Table 5). Engagement included: 8 forums; 37 group meetings; 205 site visits; 391 telephone or email enquiries. A search for “CL36 queries” and “trap” in the otter log generated 16 and 79 enquiries respectively.

Trapped otters

The trapping and removal of otters from fenced fisheries in England is illegal without the registered operatives acting under the CL36 licence. ID 38 contacted the Angling Trust/UKWOT for advice in April 27 2017, a site visit was made, a trapping application submitted to Natural England and approved.

As per licence, the boundary fence of the fishery was inspected by operatives to ascertain how the otter entered the fishery and identify any breaches to the fence which must be rectified. Attempts were then made to flush out the otter. Two seven-feet (220 L x 22 x 25 cm) double-entry traps were then secured within the fishery for just over a week. Traps were covered to make it dark inside, and baited with fish and fresh otter spraints. Once set, the traps were checked at least twice in each 24-hour period by fishery staff, in the morning and in the evening. Remote monitoring devices and cameras were used to notify UKWOT operatives when the trap doors closed.

The first otter was live trapped and released outside the fenced perimeter on May 12 2017, with the traps being left on site for a further week to ensure that no more were present (Figure 2). Two days later on May 14 2017, a second otter was live trapped and released.

Both otters were visually assessed for health following protocol. Neither was harmed or injured as a result of the humane trapping and subsequent release. With no further sightings of otters or signs of otter predation within the fishery, the traps were removed on May 23 2017. Otters are released immediately outside the fence rather than in another location as they are a protected species and it is important that their territories are not disrupted (Simpson, 2006).

In the press release on May 25 2017, Dave Webb stated: “It is pleasing that the fishery was confident enough to contact UKWOT for help. This is the first live capture of otters under the newly designed licence from Natural England and with our welfare and operating policies in place. The humane trapping and release of two otters from one fenced fishery proves that the licence can be of benefit to both otter conservation and angling. It is without doubt a major step forward for the UKWOT team who worked very hard to get this right, and for ongoing collaboration with fisheries.” Daniel Allen added: “It is important to note that UKWOT prefer not to trap otters and only do so to safeguard the welfare of this protected species. Humane trapping is only ever used as a last resort” (Allen, 2017b).

CONCLUSION

The introduction of the CL36 licence has provided a structured legal route to humanely trap otters in fenced fisheries and move them outside the fenced perimeter. With no previous published evidence on the presence of otters in fenced fisheries in England, UKWOT took a pragmatic approach, listening to concerns from those with working knowledge of stillwater fisheries and predation. As a joint initiative between UKWOT and key stakeholders from the angling community, all media coverage underlined the importance of collaboration, and stressed how the licence benefits otter conservation and fenced fisheries. In BBC Countryfile magazine, for example, Parr (2016) concluded: “In a world where so many issues become polarized, this is a landmark victory for common sense. For as long as anglers and conservationists can work together and remain proactive, the otter can be a welcome and integral part of our aquatic environment.”

In the context of fisheries and predation in England, UKWOT was fully aware of the relatively narrow scope of the licence from the outset, lobbying for the CL36 was always exclusively intended for fenced fisheries as without a formalised legal means to remove otters some fishery managers may have been tempted to illegally kill them to protect their livelihoods. The launch of the CL36 licence generated significant interest from fisheries as demonstrated by the 45 UKWOT enquiries with 6 licence applications in the first year; the fact that 22 CL36 enquiries came from unfenced fisheries suggests there was initially some confusion over the scope of the licence and/or a demand for such a service beyond the scope of the licence. The 6 enquiries with 4 licence applications in the second year and 7 with 3 licence applications so far in the third year suggests the scope of the CL36 licence has become clear.

The UKWOT ‘Interventions Spreadsheet’ and Angling Trust’s ‘Otter Log’ is evidence of the ongoing concerns about otter predation, and proves that the presence of otters in English fenced fisheries is not as “rare” as expected (OSG UK, 2016), but also not widespread. Natural England (cited in CIEEM, 2017) acknowledged that “demand to register for this new licence and the approved training has been greater than anticipated.” This led to a review of the way the licence was operated and the decision “to run further approved training under a more formal contract” (Webb, 2017).

The successful trapping and removal of two otters from a fenced fishery in May 2017 shows the CL36 licence can work in practice and that the protected otter “can be humanely managed in a non-lethal way at a local scale in England” (Allen cited in Allen, 2016), giving fenced “fisheries and anglers alike the confidence that there is a legal, humane and sensible option to help reduce otter predation” (Webb cited in Allen, May 2017).

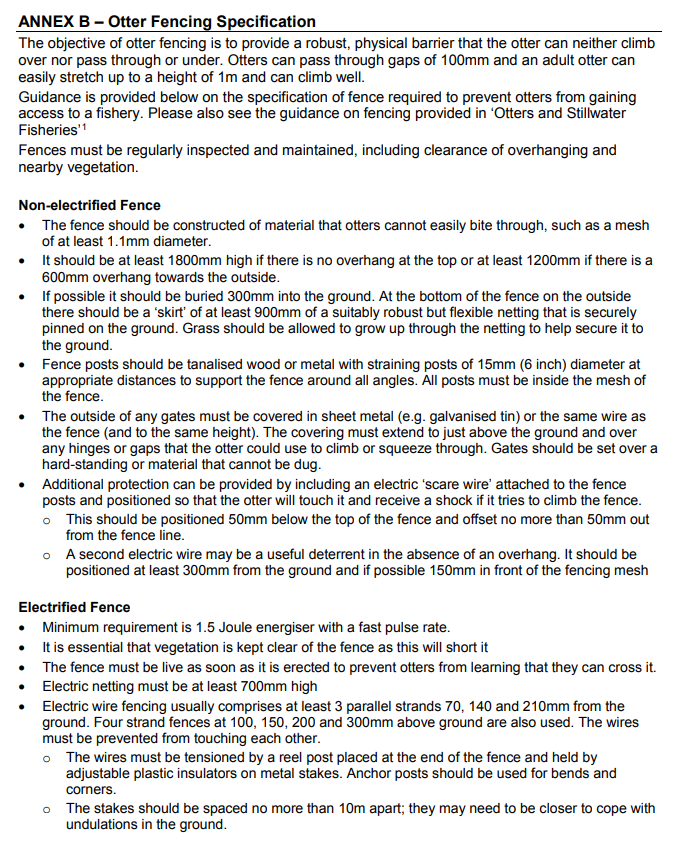

The Environment Agency and Angling Trust have advised on otter-proof fencing for over a decade (Jay et al, 2008), the CL36 licence has formalised this advice providing standardised fencing specifications for stillwater fisheries (Figure 3).

The CL36 licence has become an important bridge between fisheries, UKWOT and the Angling Trust; and useful access point for knowledge exchange about the effectiveness of otter-proof fencing, need for fencing repairs and improvements, and importance of fence perimeter management. The ongoing dissemination of advice by stakeholders contributes to the prevention of otter predation through collaboration, education and fencing, with humane traps available as a last resort.

Footnotes

[1] In March 2019 the Agreement on International Humane Trapping Standards came into force across England, Scotland and Wales. This ‘sets out clearly-defined minimum trap humaneness standards and trap testing procedures’, providing further protection to otters, badgers, beavers and pine martens (GOV.UK, 2019b).

[2]UKWOT started a monthly electronic newsletter in February 2018 to communicate charity developments.

[3] In terms of costs, the two Fishery Management Advisors trap as part of their job with the Angling Trust and work under UKWOT policy. If UKWOT trappers need to charge, Embryo Angling covers the costs of the charity.

Acknowledgements: The lead author is grateful to Keele University for funding research on ‘Fisheries, Predation and the Protected Otter’ with a Research Excellence Framework (REF) Impact Case Study Development Grant and a School of Geography Geology and Environment (GGE) Research Grant. The authors would also like to thank the licenced trapping operatives that make the CL36 licence possible, staff at the Environment Agency and Angling Trust for their ongoing collaboration and advice, and our anonymous peer reviewer and the IUCN/SSC Otter Specialist Group Bulletin editor for their useful comments and guidance.

REFERENCES

Allen, D., (2010). Otter. Reaktion Books, London.~

Allen, D., (2016). UK Wild Otter Trust secures England’s first initiative class licence from Natural England for the live capture and transport of the European Otter. LinkedIn article, September 29. Available at: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/uk-wild-otter-trust-secures-englands-first-initiative-daniel-allen/

Allen, D. (2017)a. Separating fact from fiction: anglers and otters. BBC Wildlife Magazine, online June 28 2017. Available at: https://www.discoverwildlife.com/animal-facts/mammals/separating-fact-from-fiction-otters-and-anglers/

Allen, D. (2017)b. UK Wild Otter Trust safely relocate two otters from a fenced fishery. LinkedIn article, , February. Available at: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/uk-wild-otter-trust-safely-relocate-two-otters-from-fenced-allen/

Allen, D. and Pemberton, S., (2018). Otter predation and the reproduction of rural landscape: conflict or consensus in the English countryside? RGS-IBG Annual International Conference, August 29-31 2018, Cardiff University.

Allen, D. and Pemberton, S. (2019). Perceptions on Otter Predation. Environment Agency, Bristol.

Angling Trust and Institute of Fisheries Management (2018). Otter Predation – Finding Ways Forward. AT & IFM Joint Workshop. Friday June 8th 2018. Summary & Key Outputs.

Angling Trust ( 2019). Fishery Management Advisors. Available at: https://www.anglingtrust.net/page.asp?section=1764§ionTitle=Fishery+Management+Advisors

Angling Trust Fishery Management Advisors (2019). Otter Log – April 2017 to June 2019. Angling Trust, Ilkeston.

BARB. (2019). Weekly top 30 programmes. Available at: https://www.barb.co.uk/viewing-data/weekly-top-30/

BBC One’s Countryfile (2017). Otters and fisheries item. January 15, 19:30-20:30

CARPologyTV (2016). Big otter law change. November 21, YouTube Channel. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vi5Ec3GM8Uo

Chanin, P.R.F., (1985). The Natural History of Otters. Croom Helm, Kent.

Chanin, P.R.F. and Jefferies, D.J. (1978). The decline of the otter (Lutra lutra) in Britain; an analysis of hunting records and discussion of causes. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 10(3): 305-328.

Chartered Institute of Ecology and Environmental Management (CIEEM) (2017). Natural England update on training provision to register under the Otter Class Licence. February 27. No longer available online: https://www.cieem.net/news/389/natural-england-update-on-training-provision-to-register-under-the-otter-class-licence

CL36 Licence (2016). CLASS LICENCE Otter: live capture and transport. Natural England. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/764252/cl36-otter-trapping-licence.PDF

Crawford, A. (2003). Fourth Otter Survey of England 2000—2002. Environment Agency, Bristol.

Crawford, A.K. (2010). The fifth otter survey of England 2009-10. Environment Agency, Bristol.

Embryo Angling (2016). Embryo and UKWOT partnership brings ‘humane trapping’ success. , October 6. Available at: https://www.embryoangling.org/news/embryos-partnership-ukwot-brings-step-forward/

Embryo Angling Habitats (2019). Embryo Angling Habitats website. Available at: https://www.embryoangling.org/

GOV.UK. (2016). New otter class licence issued. September 30. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/new-otter-class-licence-issued

GOV.UK. (2018). Recreational angling puts £1.4bn into English economy. October 18 2018. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/recreational-angling-puts-14bn-into-english-economy

GOV.UK. (2019)a. Otters: licence to capture and transport those trapped in fisheries to prevent damage (CL36). Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/otters-licence-to-capture-and-transport-those-trapped-in-fisheries-to-prevent-damage

GOV.UK. (2019)b. Humane trapping standards: March 2019 update. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/humane-trapping-standards-march-2019-update

Jay, S., Lane, M-R., O’Hara, K., Precey, P. and Scholey, G. (2008). Otters and stillwater fisheries. The Wildlife Trusts. Available at: https://www.anglingtrust.net/core/core_picker/download.asp?id=2526

Keeble, A. (2016). North Devon wildlife group granted ‘first ever’ licence to free trapped otters. North Devon Gazette, September 30 2016. Available at: https://www.northdevongazette.co.uk/news/north-devon-wildlife-group-granted-first-ever-licence-to-free-trapped-otters-1-4717832

Kruuk, H. (2006). Otters: Behaviour, Ecology and Conservation. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Lenton, E.J., Chanin, P.R.F. and Jefferies, D.J., (1980). Otter Survey of England 1977-79. Nature Conservancy Council, London.

McCarthy, M. (2011). Otters return to every county in England. Independent., August 18 2011. Available at: https://www.independent.co.uk/environment/nature/otters-return-to-every-county-in-england-2339626.html

O’Connor, F.B., Barwick, D., Chanin, PRF., Frazier, J.F.D., Jefferies, D.J., Jenkins, D., Neal, E. and Sands, T.S. (1977). Otters 1977: First report of the Joint Otter Group. Nature Conservancy Council and Society for the Promotion of Nature Conservation. London and Nettleham, Lincoln.

OSG UK (2016). IUCN Otter Specialist Group UK Meeting Minutes, October 15th 2016. Chestnut Centre Otter and Owl Wildlife Park, Derbyshire.

Otter Stop Ltd (2019). Otter Stop Ltd website. Available at: https://www.otterstop.co.uk/

Paisley, T. and Heylin, M. (2019). Predation. An Ecological Disaster. Big Picture Two. Predation Action Group, Lechlade.

Parr, K. (2016.) Otter problems and solutions. BBC Countryfile Magazine, October 13 2016. Available at: https://www.countryfile.com/wildlife/otter-problems-and-solutions/

Petch, T. (2016). Breakthrough over otters.’ Anglers Mail, October 14 2016. Available at: https://www.anglersmail.co.uk/news/breakthrough-over-otters-71533

Predation Action Group (2019). Otters: PAG and Otter Trapping Licences. Predation Action Group website. Available at: https://www.thepredationactiongroup.co.uk/otters

Press Association (2017). Countryfile sparks debate with segment on otters. The Press, January 15 2017. Available at: https://www.yorkpress.co.uk/leisure/showbiz/15025036.countryfile-sparks-debate-with-segment-on-otters/

Simpson, V.R. (2006). Patterns and significance of bite wounds in Eurasian otters (Lutra lutra) in southern and south-west England. Veterinary Record, 158(4): 113-119.

Strachan, R., Birks, J.D.S., Chanin, P.R.F. and Jefferies, D.J. (1990). Otter Survey of England 1984-86. Nature Conservancy Council, Peterborough.

Strachan, R. and Jefferies, D.J. (1996). Otter survey of England 1991-1994. Vincent Wildlife Trust, London.

UKWOT (2016). Class licence – otters: live capture and transport. Available at: http://www.ukwildottertrust.org/licence/

UKWOT (2019)a. Interventions spreadsheet derived from records database, October 2016 to June 2019. UKWOT, Umberleigh.

UKWOT (2019)b. UK Wild Otter Trust Facebook Group. Available at: https://www.facebook.com/groups/1407587012789673/about/

Webb, D. (2017). Demonstration of knowledge for registration to the CL36 class licence to humanely trap & relocate otters , June 7 2017. Freedom of Information request to Natural England. Available at: https://www.whatdotheyknow.com/request/demenstration_of_knowledge_for_r

Résumé : Evaluation de l’Impact de la Licence de Piégeage de la Loutre Eurasienne (Lutra Lutra) dans les Étangs de Pêche Clôturés

La loutre eurasienne (Lutra lutra), une espèce en voie de disparition, a été protégée à partir de 1978 en Angleterre et au Pays de Galles. Le rétablissement progressif de l'espèce coincide avec l’augmentation de la capture de poissons dans les étangs de pêche et l'inquiétude grandissante quant à la prédation par la loutre. Bien que la pose de clôture anti-loutre ai été identifiée comme la solution la plus efficace à moyen et à long terme, l'absence de mécanisme juridique formalisé permettant d’éloigner les loutres des étangs de pêche clôturés compromet les possibilités de survie et le bien-être des loutres. Conscient de ce problème, le Wild Otter Trust du Royaume-Uni (UKWOT) a fait pression et obtenu une licence lui permettant de les piéger et de les récupérer avec humanité. Cette publication examine les réponses initiales des médias et des intervenants suite à l’introduction par le Natural England de la «Licence de classe» CL36 permettant de capturer et transporter des loutres eurasiennes (Lutra lutra) vivantes des étangs de pêche clôturés afin de prévenir des dommages ultérieurs. La publication analyse la "feuille de calcul des interventions" de l’UKWOT pour les trois années de licence CL36 (de novembre 2016 à juin 2019) et le "Otter Log" de l’AT Fishery Management Advisors (FMA) (de mars 2017 à mars 2019) destiné à répertorier les enquêtes liées à la loutre. Enfin, la publication évalue l’impact du permis dans la pratique, en se référant au piégeage réussi et à l’enlèvement des loutres présentes dans les étangs de pêche clôturés.

Revenez au dessus

Resumen: Esquerías Cercadas, Nutrias Eurasiáticas (Lutra lutra) y Trampeo Autorizado: Una Evaluación de Impacto

La amenazada Nutria Eurasiática (Lutra lutra) pasó a ser una especie protegida en Inglaterra y Gales en 1978. La recuperación gradual de la especie coincide con el incremento del "Specimen fishing" en pesquería de aguas quietas y la creciente preocupación respecto de la predación. Aunque el cercado a prueba de nutrias ha sido identificado como la solución de mediano plazo más efectiva, la falta de un mecanismo legal formalizado para remover las nutrias de las pesquerías cercadas comprometía fuentes de trabajo y el bienestar de las nutrias. Reconociendo ésto, el Wild Otter Trust del Reino Unido (UKWOT) gestionó exitosamente una licencia para capturar nutrias humanitariamente y removerlas. Este trabajo examina las respuestas iniciales de los medios informativos y los actores involucrados, a la introducción por parte de Natural England de la Licencia CL36 para captura viva y transporte de nutrias Eurasiáticas (Lutra lutra) que son capuradas en pesquerías cercadas para prevenir daños ulteriores. El trabajo analiza el “Formulario de Intervenciones” de UKWOT para los tres años de vigencia de la licencia CL36 (Noviembre 2016 a Junio 2019) y el “Otter Log” de AT Fishery Management Advisors (FMA) (Marzo 2017 a Marzo 2019), para detectar solicitudes o consultas relacionadas con nutrias. Finalmente, el trabajo evalúa el impacto de la licencia en la práctica, con referencia a la captura viva y remoción exitosa de nutrias de pesquerías cercadas.

Vuelva a la tapa