IUCN/SSC Otter Specialist Group Bulletin

©IUCN/SCC Otter Specialist Group

Volume 42 Issue 2 (March 2025)

Citation: Karimi, A. and Badelu, N. (2025). Beyond the River: New Observations of Eurasian Otters (Lutra lutra) by the Caspian Sea. IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull. 42 (2): 98 - 103

Beyond the River: New Observations of Eurasian Otters (Lutra lutra) by the Caspian Sea

1Department of Animal Sciences and Marine Biology, Faculty of Life Sciences and Biotechnology, Shahid Beheshti University, Tehran, Iran

2Department of Environment, Faculty of Natural Resources and Environment, Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Iran

*Corresponding Author Email: alikarimimarinebiologist@gmail.com

Received 25th November 2024, accepted 27th January 2025

Abstract: The Eurasian otter (Lutra lutra), is one of the most widespread mammals in Iran, occurring in 13 provinces. They are aquatic and semi-aquatic mammals. We report here two new records of the species by the Caspian Sea, beyond their usual distribution

Keywords: Caspian Sea, Lutra lutra, marine biology, marine mammals

INTRODUCTION

The Eurasian otter (Lutra lutra) inhabits a variety of aquatic and semi-aquatic environments across Europe, Asia, and North Africa (Mousavi et al., 2023). It favors shallow, narrow sections of streams that are bordered by mature trees and rocky formations (Mousavi et al., 2023). Otters are also commonly found in rivers, streams, aqueducts, wetlands, lakes, and fish-farming ponds that support suitable vegetation (Mousavi et al., 2023). The selection of their habitat is influenced by multiple factors that vary across different geographical areas. In central Poland, field surveys conducted in 1998 and 2007 indicated a population increase, which has been positively correlated with river width and negatively impacted by the presence of human civilization (Romanowski et al., 2013). In South Korea, otters tend to inhabit areas with minimal human interference, favoring natural features such as streams with reeds, shrubs, and large boulders (Park et al., 2002). A recent study in Spain has shown that in river basins with considerable human activity, otters face a trade-off between accessing productive areas and finding well-structured, safe habitats (Tolrà et al., 2024). The suitability of habitats for otters is determined by the surrounding vegetation, the degree of human disturbance, and land use within 100 meters of riverbanks (Martin‐Collado et al., 2020). Notably, research indicates that otters do not exclusively rely on natural aquatic habitats; even renovated gravel pits can provide adequate living conditions within human-modified landscapes (Martin‐Collado et al., 2020). However, the requirements for breeding sites are more stringent than those for general habitat use, particularly concerning human disturbance (Tolrà et al., 2024).

In Iran, otters have been recorded across 13 provinces (Yusefi et al., 2019), covering a diverse range of biogeographical regions, including the Irano-Turanian, Euro-Siberian, and Saharo-Sindian regions (Djamali et al., 2011). This variety of biogeographical areas gives rise to an array of aquatic and terrestrial habitats, each contributing uniquely to the country’s ecological landscape. As a result, Iran boasts a multitude of wetlands and rivers, each characterized by its own distinct biogeographical features (Zehzad et al., 2002). The Euro-Siberian region, situated in the northern part of the country, encompasses records from Guilan, Mazandaran, and Golestan. The Irano-Turanian region, which spans much of central and western Iran, includes sightings from Tehran, Alboz, Kordestan, Kermanshah, Kohgiluyeh and Boyer Ahmad, Esfahan, Chaharmahal and Bakhtiari, Fars, and Azarbaijan W. The overlap of the Irano-Turanian and Saharo-Sindian regions is reflected in records from Khozestan (Yusefi et al., 2019). Additionally, there are also some other records from Azarbaijan E, Hamadan, Kordestan, Lorestan, Markazi, and Zanjan (Yusefi et al., 2019).

Habitat quality assessment on the Jajrood River revealed that downstream stretches are more suitable for otters (Mirzaei et al., 2009b). Habitat selection studies conducted on the Jajrood River revealed significant correlations between otter signs, altitude, and the presence of pools (Mirzaei et al., 2009a). In the Anzali wetland, otters favor quiet, less polluted areas with ample food availability (Naderi et al., 2017). Otters may have a more extensive distribution in Iran than previously believed, potentially inhabiting most rivers and lakes across the country (Gutleb et al., 1996). However, the species is threatened by environmental degradation, pollution, and conflicts with fisheries (Naderi et al., 2017). Otters are near threatened on the IUCN red list over the globe. However, they are regionally vulnerable (Yusefi et al., 2019). The presence of otters on the coasts of the sea is not a novel observation. MacDonald and Mason (1980) examined marking behavior in the coastal population of otters on a sea loch in northwest Scotland. Wales is also another country in which otter coastal activities have been recorded (Parry et al., 2011). In Iran, camera traps have captured otters in the Anzali wetland (Naderi et al., 2017). The Miankaleh Wetland is a rich wildlife refuge with special characteristics and suitable habitat for aquatic and terrestrial plants and animals (Ejtehadi et al., 2003). It is home to otters in the eastern parts of the Iranian Caspian Sea coast (Mousavi et al., 2023). However, there is no record of such in some lesser-studied areas due to insufficient funding and human resources. There are also some other reports of the species’ occurrence in various habitats of the country. In 2014, two dead individuals were found in a fish farm pond in Taleqan, and in 2015 an adult was observed in a river located in Taleqan (Mohtasebi and Tabatabaei, 2018). Taleqan is a mountain area in Alborz province with rivers and a cold climate (Mohtasebi and Tabatabaei, 2018). In Guilan, besides the observation of otters in the Anzali Wetland mentioned in the text, otters have also been studied in Amirkelayeh Wildlife Refuge, revealing that the species signs can be found throughout the year, occurring more within the areas where food is more accessible (Hadipour et al., 2011). Amirkelayeh wetland is an international wetland with 15 fish species, located south of the Caspian Sea (Khara and Sattari, 2016).

OBSERVATION

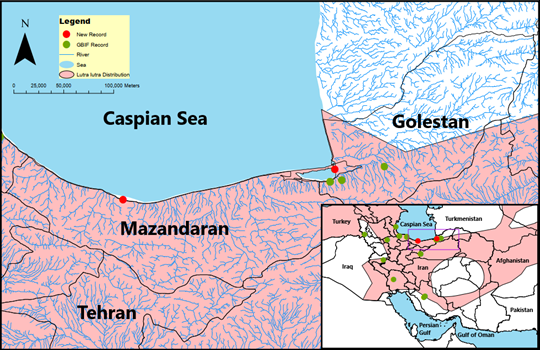

We present here two new records of otters in the Caspian Sea (Fig. 1). The Caspian Sea is the largest inland body of water in the world, home to unique wildlife (Nasrollahzadeh, 2010). The first observation was in the Miankaleh wetland in Golestan province from Behrad Farkhondeh (36°53’49’’N / 54°2’12’’E) in February 2015 at midday (Fig. 2). As it is clear in one of the photos, the otter was eating a fish. The second one is an observation by Mr. S. Kamali (36°35’58’’N / 51°40’9’’E) in Mazandaran province. He captured a video of an otter on the shoreline of the Caspian Sea in December 2020 in the daytime (Fig. 3). The locality is close to a river, from where we think the otter reached the Caspian shore. There is limited information and informal reports of the otter’s presence within the Caspian Sea from local fishermen, and the Caspian Sea hosts fish, frogs, and snakes that might attract otters. No record of otter breeding or nursing in the Caspian Sea is documented so the hypothesis of otter settlement in the Caspian Sea requires further evidence. We are not sure if the otter has been settled there or was just looking for some opportunities in its backyard.

DISCUSSION

These two observatations clearly show otter occurrence and foraging behavior by the Caspian Sea. We expect more sightings of the species in estuaries of the Caspian Sea where there is suitable vegetation and appropriate fish, frogs, and snakes around to feed on. While more studies are needed to understand how much of the otter population depends on the Caspian Sea, long-term changes in the Caspian Sea level due to anthropogenic influence and global warming by the end of the century could potentially deteriorate otter habitats (Lahijani et al., 2023). The Miankaleh wetland faces pollution, and scientists believe more attention to the wetland is needed (Mehrdadi et al., 2024). In 2020, in a mass mortality, about 38,000 waterbirds died over 50 days at Miankaleh because of Clostridium botulinum (Maken Ali et al., 2020). These changes in the habitat show an uncertain future for the rich biodiversity of the Miankaleh such as otters. We suggest more research on otters in such regions to understand how to safeguard their future, and to use them as indicators to predict the future of the habitats of Caspian Sea coasts.

CONCLUSIONS

Acknowledgment - We would like to thank Behrad Farkhondeh and Shahab Kamali for sharing their photos and videos. We dedicate this manuscript to the memory of Behrad Farkhondeh, who was a prolific wildlife photographer and tragically passed away in an accident. We would like to express our sincere gratitude to Danial Nayeri for his invaluable assistance and guidance in the preparation of this manuscript.

Author contributions - All authors contributed to the study design and conceptualization. The first draft of the manuscript was written by the first author. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests - The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Research funding - This research received no financial support.

Research ethics - The research did not involve human participants. The authors confirm that their results are original and follow ethical principles in the data collection.

REFERENCES

Djamali, M., Akhani, H., Khoshravesh, R., Andrieu-Ponel, V., Ponel, P., & Brewer, S. (2011). Application of the global bioclimatic classification to Iran: implications for understanding the modern vegetation and biogeography. Ecologia mediterranea, 37(1): 91-114. http://dx.doi.org/10.3406/ecmed.2011.1350

Ejtehadi, H., Amini, T., Kianmehr, H., and Assadi, M. (2003). Floristical and chorological studies of vegetation in Myankaleh wildlife refuge, Mazandaran province, Iran. Iranian International Journal of Science 4: 107–120 https://iijs.ut.ac.ir/article_30958_eb6786efd6cf327d9a2a5178e29a72cb.pdf

Gutleb, B., Rautschka, R., and Gutleb, A. C. (1996). Some comments on the otter (Lutra lutra) in Iran. IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull, 13: 43-44. https://www.iucnosgbull.org/Volume13/Gutleb_et_al_1996.html

Hadipour, E., Karami, M., Abdoli, A., Borhan, R. and Goljani, R. (2011). A Study on Eurasian Otter (Lutra lutra) in Amirkelayeh Wildlife Refuge and International Wetland in Guilan Province, Northern Iran. IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull. 28 (2): 84 – 98 https://www.iucnosgbull.org/Volume28/Hadipour_et_al_2011.html

Khara, H. and Sattari, M. (2016). Occurrence and intensity of parasites in Wels catfish, Silurus glanis L. 1758, from Amirkelayeh wetland, southwest of the Caspian Sea. J Parasit Dis 40: 848–852 https://doi.org/10.1007/s12639-014-0591-7

Lahijani, H., Leroy, S., Arpe, K., and Cretaux, J.-F. (2023). Caspian Sea level changes during instrumental period, its impact and forecast: A review. J. Earth-Sci Rev, 241: 104428. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2023.104428

Macdonald, S., and Mason, C. (1980). Observations on the marking behaviour of a coastal population of otters. J. Acta Theriol, 25(19): 245-253. https://rcin.org.pl/ibs/publication/26453

Maken Ali, A. S. , Heidarnejad, O. , Keshavarz Zamanian, V. , Habibi, M. , Rabiei, K. , Talifar, H. and Abdolahi, H. (2020). A Comprehensive Monitoring of The High Mortality Rate of Wild Waterbirds in Miankaleh Wetland in 2020. Veterinary Research & Biological Products, 33(3): 130-139 https://doi.org/10.22092/vj.2020.343532.1736

Martin‐Collado, D., Jiménez, M. D., Rouco, C., Ciuffoli, L., and de Torre, R. (2020). Potential of restored gravel pits to provide suitable habitats for Eurasian otters in anthropogenic landscapes. J. Restor Ecol, 28(4): 995-1005. https://doi.org/10.1111/rec.13129

Mehrdadi, M., Mehrdadi, N., Amiri, M. J. (2024). Assessing Land Use Change Impact on Ecosystem Services (Case Study: Wetland And Biosphere Reserve of Miankaleh). Geography and Environmental Sustainability, 14(4): 103-121 https://doi.org/10.22126/ges.2024.11109.2786

Mirzaei, R., Karami, M., Danehkar, A., and Abdoli, A. (2009) a. Habitat selection of the Eurasian Otter, Lutra lutra, in Jajrood river, Iran: (Mammalia: Carnivora). J. Zool Middle East, 47(1): 13-19. https://doi.org/10.1080/09397140.2009.10638342

Mirzaei, R., Karami, M., Danehkar, A., and Abdoli, A. (2009) b. Habitat quality assessment for the Eurasian otter (Lutra lutra) on the river Jajrood, Iran. J. Hystrix, 20(2). https://doi.org/10.4404/hystrix-20.2-4447

Mohtasebi , S and Tabatabaei, F (2018). Evidence of the Presence of Lutra lutra in Taleqan, Alborz Province, Iran . IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull. 35 (3): 156 – 158 https://www.iucnosgbull.org/Volume35/Mohtasebi_Tabatabaei_2018.html

Mousavi SP, Ramzanipour MM, Vajargah MF (2023). An Overview on Lutra lutra. J Biomed Res Environ Sci., 4(4): 714-718. http://dx.doi.org/10.37871/jbres1728

Naderi, S., Mirzajani, A., and Hadipour, E. (2017). Distribution of and threats to the Eurasian Otter (Lutra lutra) in the Anzali Wetland, Iran. IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull, 34(2): 84-94. https://www.iucnosgbull.org/Volume34/Naderi_et_al_2017.html

Nasrollahzadeh, A. (2010). Caspian Sea and its ecological challenges. J. Caspian Journal of Environmental Sciences, 8(1): 97-104. https://cjes.guilan.ac.ir/article_1037.html

Park, C.-H., Joo, W., and Seo, C.-W. (2002). Eurasian otter (Lutra lutra) habitat suitability modeling using GIS; A case study on Soraksan National Park. Spatial Information Research, 10(4): 501-513.

Parry, G. S., Burton, S., Cox, B., and Forman, D. W. (2011). Diet of coastal foraging Eurasian otters (Lutra lutra L.) in Pembrokeshire south-west Wales. J. Eur J Wildlife Res, 57: 485-494. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10344-010-0457-y

Romanowski, J., Brzeziński, M., and Żmihorski, M. (2013). Habitat correlates of the Eurasian otter Lutra lutra recolonizing Central Poland. J. Acta Theriol, 58: 149-155. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s13364-012-0107-8

Tolrà, A., Ruiz-Olmo, J., and Riera, J. L. (2024). Human disturbance and habitat structure drive Eurasian otter habitat selection in heavily anthropized river basins. J. Biodivers Conserv., 33(5): 1683-1710. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10531-024-02826-9

Yusefi, G. H., Faizolahi, K., Darvish, J., Safi, K., and Brito, J. C. (2019). The species diversity, distribution, and conservation status of the terrestrial mammals of Iran. J. Mammal, 100(1): 55-71. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jmammal/gyz002

Zehzad, B., Kiabi, B. H., and Madjnoonian, H. (2002). The natural areas and landscape of Iran: an overview. Zoology in the Middle East, 26(1): 7-10. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09397140.2002.10637915

Résumé: Au-delà de la Rivière : Nouvelles Observations de Loutres Eurasiennes (Lutra lutra) au bord de la Mer Caspienne

La loutre eurasienne (Lutra lutra) est l’un des mammifères les plus répandus en Iran où elle est présente dans 13 provinces. Ce sont des mammifères aquatiques et semi-aquatiques. Nous rapportons ici deux nouvelles observations de l’espèce au-delà de son habitat habituel près de la mer Caspienne.

Revenez au dessus

Resumen: Más Allá del Río: Nuevas Observaciones de Nutria Eurasiática (Lutra lutra) sobre el Mar Caspio

La Nutria Eurasiática (Lutra lutra) es uno de los mamíferos más ampliamente distribuidos en Irán, ocurriendo en 13 provincias. Son mamíferos acuáticos y semi-acuáticos. Reportamos aquí dos nuevos registros de la especie sobre el Mar Caspio, fuera de su hábitat más común.

Vuelva a la tapa